EXCLUSIVE: New Files Show Brazil’s Supreme Court Illegally Used Social Media Posts To Frame Pro-Bolsonaro Protesters As Insurrectionists

High court’s misrepresentation of January 8, 2023 riot as a “coup” is central to Lula government’s plans to stay in power

Friends — This important investigation, written by David Agape and Eli Viera, and edited by Alex Gutentag, includes a special report published today by Civilization Works, a nonprofit research organization, that can be read here. We have made it free for all readers. Please subscribe now to Public to support our investigative work and consider making a tax-deductible donation to Civilization Works. — Michael

P.S. Para ler este artigo em português, clique aqui.

US President Donald Trump’s 50% tariffs on Brazil, which are set to go into effect on Wednesday, August 6, are “unacceptable blackmail,” says Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The Trump administration cited Brazil’s prosecution of former president Jair Bolsonaro as a significant reason for the proposed tariffs. In response, Lula said on X that Brazil is “a sovereign country with independent institutions and will not accept any tutelage.” Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who is leading Bolsonaro’s prosecution, was put under sanctions by the US last week, a move he says is part of a “cowardly and treasonous” plot.

Bolsonaro currently faces charges related to his alleged effort to stage a coup and overturn the 2022 election results on January 8, 2023. Last month, Moraes ordered Bolsonaro to wear an electronic ankle monitor and prohibited him from using social media and communicating with other individuals under investigation.

These measures are necessary, say Brazilian authorities, because Bolsonaro could attempt to flee the country or interfere with the judicial process. The prosecution of Bolsonaro and the January 8 rioters, insists Lula, is a legal matter that is not politically motivated.

But now, new documents reveal that the Brazilian Supreme Court, known as the STF, created a secret and illegal task force that used the social media posts of nonviolent January 8 protesters as justification for investigations and imprisonments. The January 8 Files and accompanying report provide evidence that STF Justice Alexandre de Moraes overprosecuted January 8 protesters to inflate allegations of criminal activity and to legitimate Lula’s claim that the riot was a coordinated coup attempt.

All of this is significant because the coup charge is Moraes’ justification for preventing Bolsonaro from speaking to the media, and for requiring him to stay home during most hours. In June 2023, Moraes also cast one of the five votes at the Superior Electoral Court (TSE) he headed, which made Bolsonaro unable to run in elections for 8 years.

The STF and Lula have long claimed that the prosecution of Bolsonaro and his supporters was based on sound legal evidence, not political vendettas, but the January 8 Files expose these prosecutions as fundamentally political.

These documents reveal that, rather than an independent legal process, the investigation into January 8 was partisan and driven by political interests. Contrary to Lula’s claims of an independent judiciary seeking to uphold the democratic process, alleged rioters were evaluated for detention and kept in jail based on their political views, and often for simply criticizing Lula.

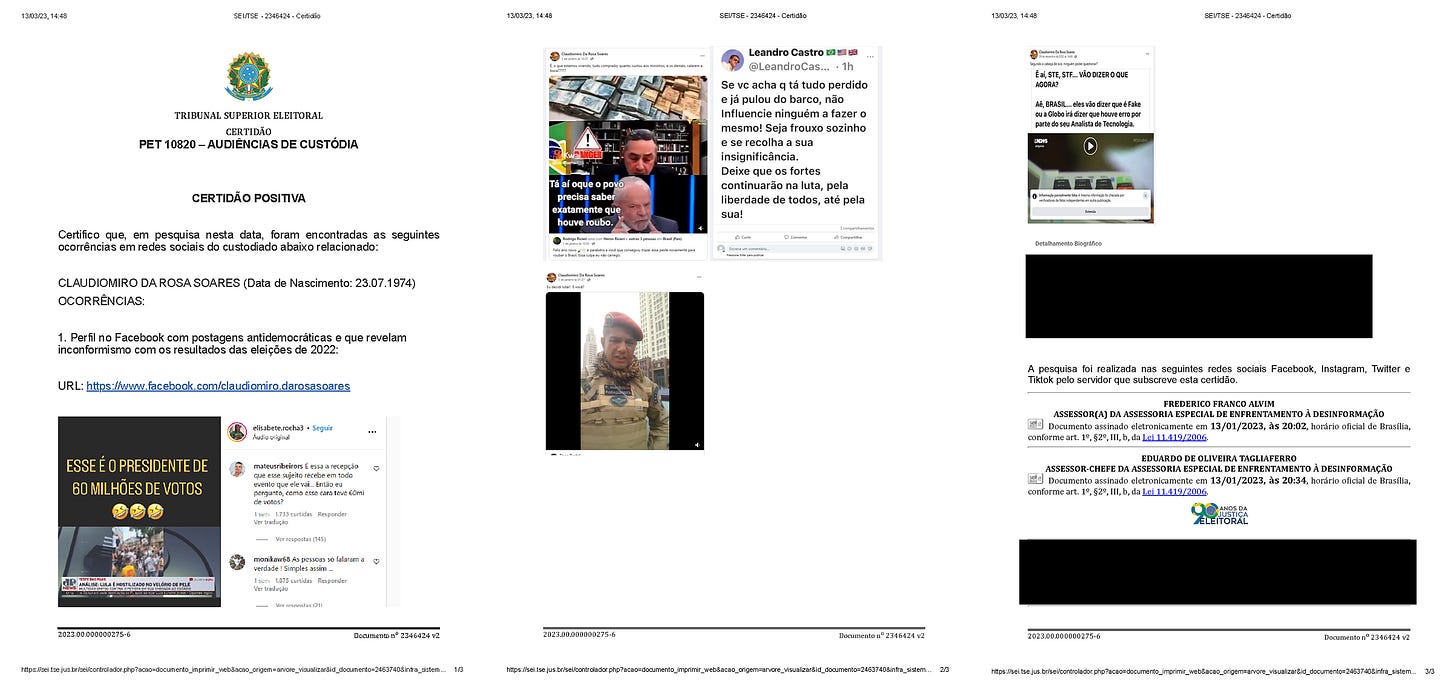

For example, Moraes’ illegal task force flagged a truck driver for a series of Facebook posts that criticized Lula and questioned the 2022 election. Accused of “violent attempt against the democratic state,” the man spent 11 months and 7 days in jail without ever committing a violent act.

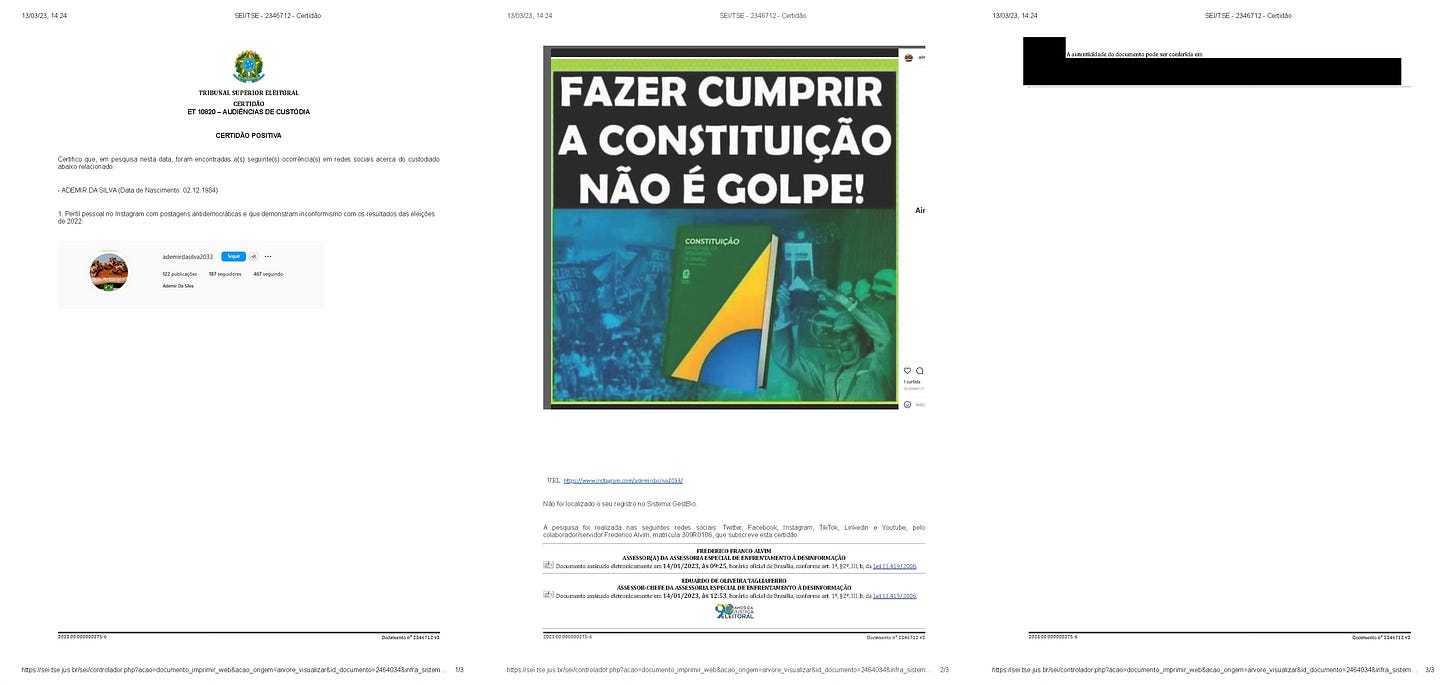

Another man was incarcerated for a single Instagram post. The post read: “Enforcing the Constitution is not a coup.”

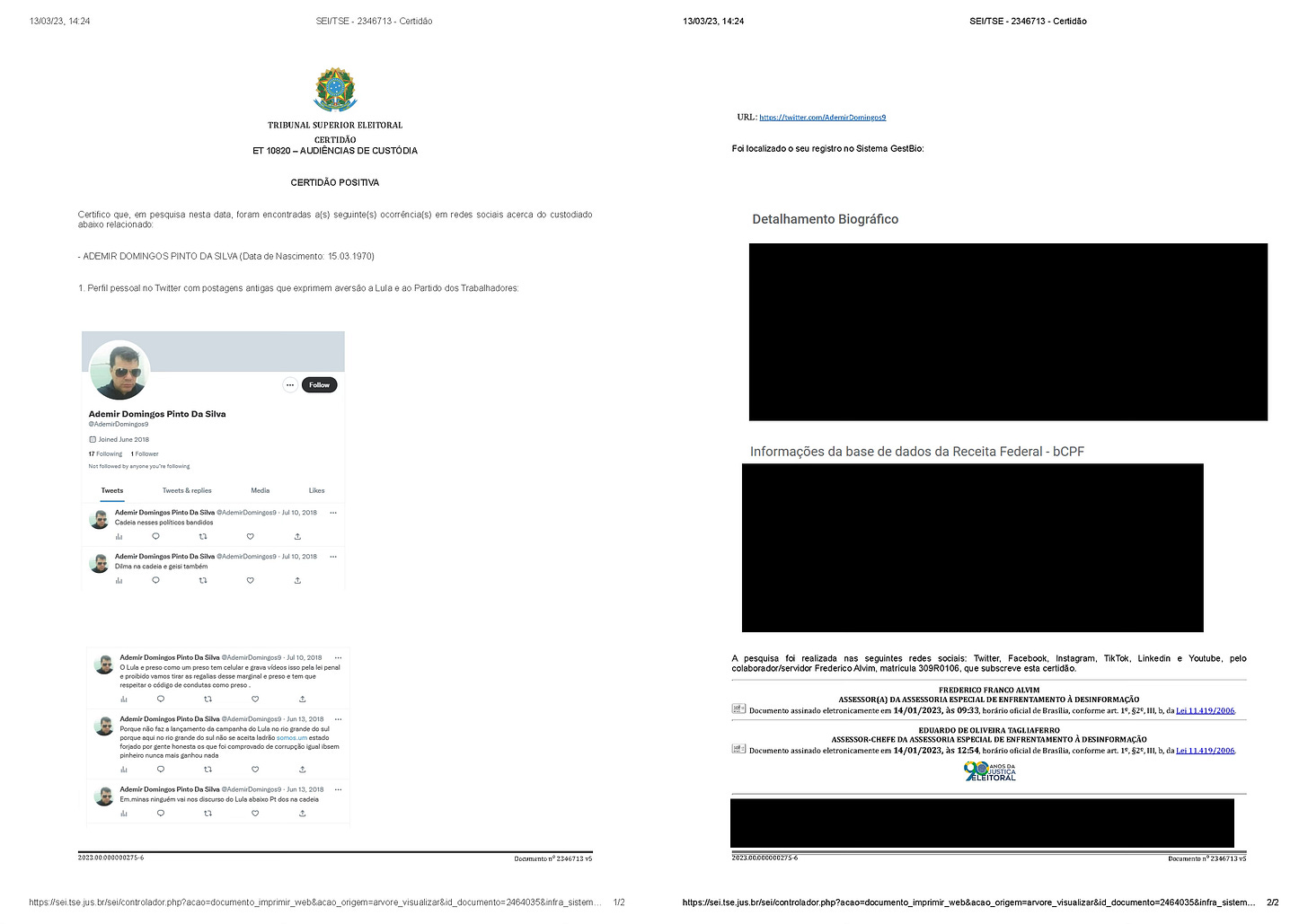

In another case, a 54-year-old street vendor from southern Brazil wasn’t even present at the January 8 riots and instead arrived later that night at a camp set up by protestors by the Army HQ in Brasília to sell flags and T-shirts. Police detained him, and the task force issued a secret report that was used as the basis for keeping him in detention for tweets from 2018 criticizing Lula and his Workers’ Party. None of these tweets mentioned January 8 or even the 2022 election. He spent four months in prison and now wears an ankle monitor.

The January 8 Files come from the same trove of text messages and other documents that journalists Glenn Greenwald and Fábio Serapião reported on for the Folha de São Paulo last August, known as the “Vaza Toga” (judicial leaks) scandal. Their reporting revealed that Moraes had expanded judicial powers to target political opponents, making himself investigator, prosecutor, and judge. Vaza Toga’s trove of text messages and audio recordings showed that Moraes had accessed confidential police records to create off-the-record intelligence reports and to justify the prosecution of Bolsonaro supporters without formal legal orders.

In response to the Vaza Toga scandal, Moraes opened a secret investigation into the leak, refused to return a seized phone from his aide, and faced no accountability, while the STF’s president dismissed the evidence as a “fictitious storm.”

But the January 8 Files show something that has not yet been reported: as part of Moraes’ sweeping, illegal effort, his investigators used political speech on social media to determine which January 8 protesters would be investigated, prosecuted, and sentenced to prison. This evidence of the court’s abuse of powers in service of Lula’s government has major implications for US-Brazil relations and ongoing trade negotiations.

In the weeks following the January 8 arrests, hundreds of detainees remained in jail — even when the Prosecutor General’s Office formally recommended their release. Lawyers, families, and public defenders had no clear explanation for why the requests were being ignored.

Attorney Ezequiel Silveira, from Association of Families and Victims of January 8 (ASFAV), who represents dozens of defendants accused in connection with the events of January 8, noted that legal deadlines were ignored, with delays of up to 22 days, violating the Code of Criminal Procedure, which requires a hearing within 24 hours of arrest. What public defenders and attorneys suspected, but could not yet prove, can now be confirmed by the January 8 Files. The real reason behind the delays was that Moraes was waiting for his task force to complete informal digital scans of defendants’ social media.

The court’s use of online speech as a secret basis for prosecution was explicit. On February 13, 2023, Moraes’ chief of staff bluntly told an internal WhatsApp group, “The Prosecutor General’s Office asked for [protesters’] release, but the Justice doesn’t want to let them go before we check their social media.”

On March 1st, 2023, Judge Airton Vieira, an aide to Moraes, sent a farewell message to the WhatsApp group. He had just wrapped up his role overseeing the custody hearings for the January 8 detainees.

Wrote one judge to the WhatsApp group after overseeing custody hearings for the January 8 detainees, “I’ll say my goodbye here, since I’ve already done so in the other groups… May we give each person what they deserve: prison! 😜😜😜😜😜.” The judge had been tasked with ensuring fairness, but his private messages revealed his prior judgment and the cynicism behind an operation that suspended due process while pretending to uphold it.

His reference to “other groups” hinted at something else: the existence of multiple parallel chats beyond the one now leaked. According to our sources linked to the TSE, there were indeed several other WhatsApp groups used to discuss official matters — all part of a broader, compartmentalized network operating outside of established legal boundaries.

Using social media posts in decisions to prosecute both rioters and nonviolent protesters, the court charged many individuals with serious crimes, including “attempted coup d’état.” Some of these cases, secretly predicated on political speech, resulted in long prison sentences. In addition, the STF illegally used the Election Court’s biometric database, GestBio, to identify protesters.

We requested comments from the STF, the TSE, the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Brazilian Army, Moraes, and other individuals in the WhatsApp group. None responded by the time of publication.

Legal scholars contacted by Public confirmed that the STF’s creation of secret intelligence reports and use of social media posts to determine which individuals to prosecute was a clear violation of multiple protections by the Brazilian Constitution.

“What was meant to be a technical and neutral body, focused on preserving the integrity of the electoral process,” said Richard Campanari, a legal scholar, “was turned into an informal mechanism of political repression. The Electoral Court’s policing power is limited to the form and medium of campaign advertising — never the content of political expression, and certainly not outside the electoral period.”

A former Supreme Court Justice, Marco Aurélio Mello, told Public, “The Constitution is clear: only the judicial police and public prosecutors are authorized to investigate crimes. When the TSE assumes this role, it oversteps its jurisdiction and distorts the criminal justice model.”

“What kind of custody hearing is it if the presiding judge doesn’t even have the power to review the legality of the arrest?” asked Enio Viterbo, a specialist in constitutional and political law.

The STF’s secret task force operated through a WhatsApp group, and its participants created informal “reports” based in part on social media posts by the accused. Notably, they did not share these reports with either prosecutors or defense attorneys.

Through digital signature URLs, we were able to confirm the authenticity of all 69 reports we obtained from the files. The links lead to the entirety of each report hosted at TSE’s website on open but unlisted URLs. We have archived all of them, but they won’t be disclosed due to sensitive personal data of the investigated.

A source close to the investigation told us that people who had posted pro-Bolsonaro content, worn green and yellow (Brazilian flag colors), followed right-wing pages, or criticized the elections were marked as “positive.”

According to the STF, out of the 1,406 people arrested after January 8, 942 had their detention converted into preventive custody. Only 464 were granted provisional release.

Our team analyzed the spreadsheets used by the task force to classify detainees. Based on the reports we were able to access, among 1,879 unique names, 319 individuals were issued some form of digital report. Eduardo Tagliaferro, the head of the Electoral Court’s Special Unit for Combatting Disinformation (AEED), said in the leaked WhatsApp chat that a total of 1,398 reports were issued.

Of the records we reviewed, 42 people were tagged “positive” and 277 “negative.” We then crossed the data with two lists issued by the STF: one for those who were released and another for those who were sent to prison after the hearings. Out of the 319 individuals who had a digital report, 251 were on either of the two lists (36 positive, 215 negative). The main pattern observable with our sample is that while a negative report was no guarantee of release, not a single person who was issued a positive report was released. This means that political opinion was effectively treated as a crime. Positive reports did not show evidence of criminal activity and wrongdoing, but instead focused on protesters’ political speech and loyalty to Bolsonaro.

Even among the “negatives,” 68% were also kept behind bars. The individuals detained included a 55-year-old engineer and ordained pastor from São Paulo who went to Brasília on January 8 to pray with a group of pastors. The court sentenced her to 17 years in prison. She spent seven months in pre-trial detention, lost her home, and developed signs of colon cancer while in custody. Another was a mother of two young children, who STF convicted to 17 years in prison.

The Twitter Files Brazil discovered that, in the years leading up to the 2022 election, the Superior Electoral Court pressured platforms to hand over user data, including IP addresses. The court orders targeted citizens who posted hashtags critical of the Brazilian electronic voting machines.

What the Twitter Files exposed as exceptional — the targeting of people for their political opinions — is now revealed as a pattern by the January 8 Files. The final batch of reports was completed on March 13, 2023, after which the WhatsApp group became inactive. Task force members engaged partisan political activists and fact-checking agencies, infiltrated private group chats, and emailed Moraes’ personal email account in an activity similar to that of journalist and academic Letícia Sallorenzo, who previously compiled lists of targets and sent them directly to the court. In her academic work, she defended online censorship.

“Brazil is witnessing, with alarming passivity, the expansion of judicial power beyond constitutional limits,” said Campanari.

How could such a thing occur in a nation with constitutional protections of due process and an independent judiciary? How is Moraes getting away with what he’s doing?

The Making of a “Coup”

On January 8, 2023, Brazil faced its own version of January 6. Hundreds of Bolsonaro’s supporters stormed government buildings in Brasília. They were angry at alleged election fraud and the return to power of a politician, Lula, who two courts had convicted of corruption.

Although vandalism and clashes with security forces did occur, many of the alleged rioters were elderly and none were armed. And yet, within hours, the STF and much of the press had classified the event as an “attempted coup” and labeled protesters as “terrorists” and “fascists.”

What came next was an unprecedented crackdown: mass arrests, censorship orders, and the concentration of extraordinary powers in the hands of Moraes, the same judge who, twenty months later, ordered the shutdown of the social media platform X in Brazil for 40 days, and is now world-famous for banning journalists and opposition politicians from social media.

Moraes held two powerful roles at the same time: Supreme Court Justice and President of the Superior Electoral Court, the body that oversees elections in Brazil. As president of the Electoral Court, Moraes affirmed Lula’s electoral victory and has since then acted in close alignment with Lula, blurring the lines between the judiciary and the executive. To serve Lula’s political interests, Moraes used his dual position in the Supreme and Electoral courts to bypass legal boundaries, turning court officials into a de facto intelligence unit.

Although the operation was directed from his STF office, key tasks fell to the Electoral Court’s disinformation team, which had no jurisdiction over criminal matters and which the TSE had created originally to monitor online election content.

Official records show that the police arrested 243 people on January 8 inside or nearby government buildings and charged them with extremely serious crimes, including damage to public property, violent abrogation of the democratic rule of law, and participation in a criminal organization. Justices later sentenced some of them to up to 17 years in prison, despite not having even committed an act of vandalism.

Simply walking through Congress was enough for some protesters to be charged with trying to overthrow the government. Three homeless individuals, children and elderly people with serious health conditions, were among those detained.

The STF also imposed a collective fine of nearly $6 million that all 643 of those convicted so far have to pay, regardless of their individual actions.

On January 9, police detained another 1,929 people who had protested peacefully at camps near the Army HQ. On the authorities’ orders, the Army officers lied to them, claiming they would be taken to the bus station to return home. Instead, they handed them over to the police, who drove them directly to prison. The Brazilian Army had previously said, publicly, that it viewed the protests as constitutionally protected expressions of free speech.

The January 8 prosecutions revealed a two-tier judicial system. In 2006, a group of left-wing activists stormed Congress, overturned cars, smashed doors, destroyed property, and seriously injured staff, including a security guard who suffered a fractured skull. Then-President Lula called their actions “vandalism” — a term now treated as too lenient for the January 8 protestors — but worked behind the scenes to secure their release. Most of the perpetrators were freed within weeks. At the time, Moraes described the left-wing protests as “criminal acts,” but not an institutional threat, and supported sentences of up to four years, unlike the 17-year terms imposed today.

In 2014, left-wing activists attempted to invade the Supreme Court (STF), injured several police officers, and forced the suspension of a session. President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s political heir, invited their leaders into her office the next day. No mass arrests necessary.

Over the past decade, left-wing groups have carried out dozens of invasions and acts of vandalism against public buildings, often leaving a trail of destruction, rarely facing collective indictments or the harsh sentences now handed down to the January 8 defendants.

Legal experts contacted by Public unanimously agreed that Moraes overstepped constitutional limits after January 8, effectively transforming the Electoral Court into an illegal shadow justice system that decided who stayed in jail not through hearings but through hastily compiled social media scans.

Sources described how the process worked. The STF received lists of names from the Federal Police. Staff then pulled data from Brazil's Federal Revenue Service database (bCPF) and the National Driver’s License Registry (RENACH). They also accessed internal systems like GestBio, the Electoral Court’s biometric voter database, which contains facial images, fingerprints, and personal data for nearly every adult Brazilian – a database that not even the Federal Police had.

After the January 8 events, Moraes issued a formal order authorizing the use of internal Electoral Court databases by the STF. The disinformation team then used GestBio to identify protesters based on images.

Accessing biometric data without a proper judicial order or explicit legal authorization is illegal, according to constitutional lawyer Richard Campanari, a member of the Brazilian Academy of Electoral and Political Law. The law requires that the GestBio system only be used for electoral purposes, such as preventing duplicate voter registrations.

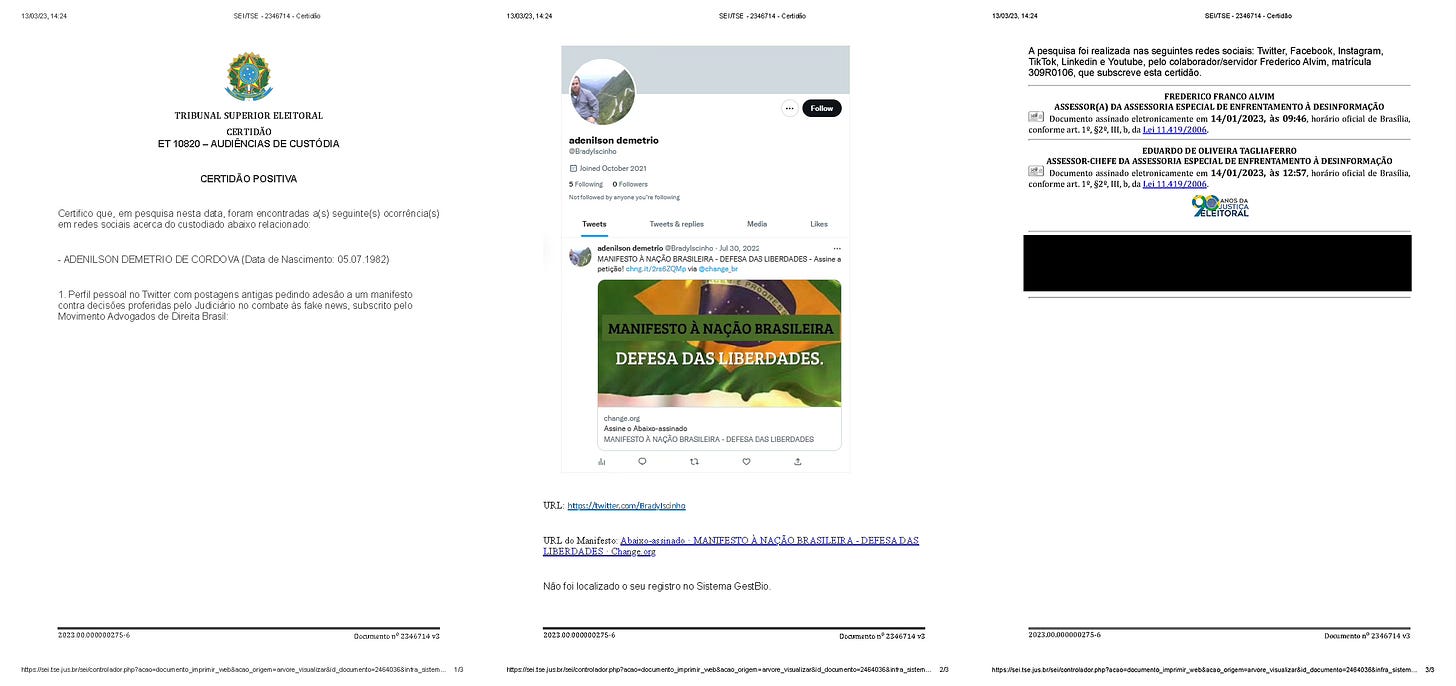

The goal of this search was to find a recent photo of each detainee. Once they matched a name to a face, the team scoured social media platforms for posts that could be interpreted as “anti-democratic.” The criteria changed from case to case. The standard was whatever the team could find. It might include sharing social media posts about the protests, criticizing the STF or President Lula, participating in a Telegram or Whatsapp group, or sharing election-related content labeled “disinformation.”Each report was based on quick searches across platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, Telegram, and Gettr. If any content was found, the detainee received a “positive report.” The main sources used to justify the labels were often news articles and anonymous Twitter profiles — frequently with no verification of authorship or context.

Errors were common. In one case, a woman named Vildete was mistakenly flagged as “positive.” Minutes later, the team realized they had confused her with someone else and changed her label to “negative.” The woman was likely Vildete da Silva Guardia, a 74-year-old retiree who became one of the most symbolic victims of judicial abuse. Even with a corrected report, she remained in jail — and was only released 21 days later due to severe intestinal bleeding.

In another case, Adenilson Demetrio de Cordova received a “positive” label because of a single post found on X. It linked to a petition titled “Manifesto to the Brazilian Nation – In Defense of Liberty,” published months before the 2022 election by a profile with zero followers and zero views.

An even more absurd case involved another Ademir — this time Ademir Domingos Pinto da Silva, a 54-year-old street vendor from southern Brazil. He wasn’t even present at the January 8 riots. He arrived later that night at the military camp in Brasília, after the storming had ended, just to sell flags and T-shirts. Police blocked him from leaving, and he was detained. He was labeled “positive” not for any act of violence, but for tweets from 2018 criticizing Lula and the Workers’ Party. None of them mentioned January 8 — or even the 2022 election.

Still, his report was signed by the disinformation unit and used to justify four months in prison and a criminal conviction. He now wears an ankle monitor and is required to complete community service. His lawyer called the case “a shameful stain on the Supreme Court” and said Ademir was convicted “without a single justice reading his file.”

Our sources revealed that Moraes’ Chief of Staff, Cristina Yukiko Kusahara, acted as Moraes’ informal representative, despite holding no official position within the court. “She basically told the judges what to do,” said one individual involved in the process.

Kusahara imposed strict control and urgency. She provided the document templates and directed the flow of communication between investigators. She made clear that the goal was to determine who should stay in jail and who might be released.

Kusahara’s orders were relentless. She dictated the pace and pushed for volume over accuracy. When Tagliaferro raised concerns, pointing out that his team was never trained to conduct intelligence work, Kusahara wrote, in a text message, “I need this done with caution, but not at your TSE pace. Sorry to say, but you guys are spoiled.”

Tagliaferro responded by explaining that his unit had originally been designed for another purpose under Frederico Alvim, the previous head of the disinformation division.

Said Kusahara, “Fred should have been fired months ago.”

Responded Tagliaferro, “Yes, he’ll be removed — just not in the middle of the storm.”

In a voice message sent to another STF Judge, Airton Vieira, Tagliaferro complained that the workload was unsustainable and that the orders from Moraes were “simply inhumane.”

Kusahara left no doubt about the purpose of the operation. “We have 1,200 detainees, and most will be released,” she wrote. “We can’t afford to sit around philosophizing.”

By “philosophizing,” Kushara referred to mounting concerns among staff about duplicated names, technical failures, and the speed of the process.

The messages show staff receiving informal detainee lists including names, photos, and ID numbers from the Federal Police without any formal chain of custody.

In one audio clip, a federal police officer asked to keep it confidential because the data was “in high demand.” The request revealed awareness that the material was being shared outside proper legal channels.

Kusahara has been Moraes’ most trusted aide since 2019, and in 2023, the Brazilian Army publicly honored her with an award for civilians who render distinguished service to the military. The Vaza Toga Files revealed that Kusahara suggested the strategy of disguising Moraes’s orders as requests from the Electoral Court.

Other aides contributed to the investigation but rarely appeared in the group’s conversations. Their mission: to profile 1,400 detainees in bulk, using any available digital footprint — and do it fast. Chief among them was Tagliaferro, who coordinated few assistants who produced the reports based on social media searches and data scraped from court databases.

Legal Experts Fight Back

One of the most vocal critics of Moraes is the former Justice Mello, who has repeatedly condemned the concentration of power in the STF and the lack of transparency exposed by the Vaza Toga scandal. Mello considers the sentences handed down to January 8 protesters disproportionate. “I cannot understand how they can be sentenced to 15, 16, 17 years in prison,” he said. “Those are sentences for murderers or armed robbers, not for rioters or vandals.”

According to attorney André Marsiglia, a freedom of expression specialist, it’s illegal for the Electoral Court to produce reports that influence judicial decisions, such as the arrest or release of January 8 defendants. He argues that the task of investigating and building a case belongs solely to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which must remain independent from the court that issues rulings.

“The body responsible for judgment cannot be the same one producing the evidence,” he said. “This represents an unconstitutional takeover of prosecutorial functions — a distortion typical of authoritarian regimes, where the law is weaponized as a tool of revenge.”

Such a delegation of investigative power is inherently illegitimate. “Once an investigative body is subordinated to the same court that will later judge the case,” he explained, “the entire process is tainted from the start — undermining the fundamental principle that those who prosecute must be separate from those who rule.”

Attorney Silvio Kuroda, Expert in Public Law and former adviser to a Justice of Brazil’s Superior Court of Justice, agreed. “It cannot be admitted that an Electoral Judiciary body, under the pretext of combating disinformation, carries out investigative measures aimed at collecting evidence regarding the authorship and materiality of criminal offenses.”

Attorney Hugo Freitas, a master of laws from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), noted that Brazil’s Constitution only allows preventive detention when needed to protect public order. “In practice, the State is granting or denying freedom based on citizens’ ideological views,” he said. “That is incompatible with the Constitution, which upholds equality and prohibits all forms of political or ideological censorship,” he said, citing Article 220, paragraph 2.

“The justice system should exist to investigate and punish crimes as defined by law,” he said. “But this case reinforces the perception that the Supreme Court, the Prosecutor General’s Office, and the Federal Police are using it for political purposes. That is unconstitutional. The State cannot assume powers beyond what the law allows.”

He cited as an example the non-prosecution agreements offered to many January 8 defendants, which required them to attend a “course on democracy.” Said Freitas, “The State has no authority to force citizens into reeducation sessions. The Constitution does not grant it the power to control people’s ideologies. Citizens are free to think as they wish — even to oppose democracy itself. What the law allows is only the repression of specific criminal acts.”

Ives Gandra da Silva Martins, a respected 90‑year‑old law scholar, said he breaks with Moraes’ “neo‑constitutionalist” doctrine. He argues that Moraes’ approach is “more at home in parliamentary systems than in Brazil’s firmly presidential one, and it blurs the Constitution’s clear separation of powers.” By turning the task‑force into what Gandra calls “a kind of guardian of what may or may not be said in Brazilian democracy,” Moraes has assumed a level of power the charter never intended.

Under Moraes’ authority, Brazil’s judiciary has become politicized to advance the goals of president Lula and his political allies. The January 8 Files show that the Brazilian Supreme and Electoral courts, far from upholding free and fair elections, have undermined basic civil liberties, the Constitution, and the rule of law. By using political speech as a basis for incarcerating protesters, the courts justified arrests and prosecutions, manufacturing the appearance of a “coup.” Moraes’ continued prosecution of Bolsonaro, in coordination with president Lula, for this manufactured allegation, represents a major threat to democracy.

Netflix released a documentary called “Apocalypse in the Tropics” about Brazil. It portrays Lula and de Moraes as defenders of democracy against the villain Bolsonaro. Who is funding this propaganda? https://yuribezmenov.substack.com/p/brazil-apocalypse-in-the-tropics-propaganda

Gosh, it is so good to know we in the US would never see this sort of thing - an evil, authoritarian government imprisoning (even killing) political opponents….

Oh wait…. Jan 6, Jan 8….