Why Drug Decriminalization Failed

Plus: How to Get Drug Policing Right

Proponents of “decriminalizing” drugs claimed that doing so would help get sky-high overdose death rates under control. Decriminalization, they said, would allow drug users to come out of the shadow of criminalization to seek the treatment they needed. Oregon, British Columbia, and Washington State adopted such measures in North America’s first experiment with drug decriminalization, replacing criminal penalties for possession with fines or other civil remedies.

But in the last couple of months, these audacious experiments in drug policy have collapsed. In April, Oregon officially repealed key parts of Measure 110, the 2020 ballot initiative that had made possession of small quantities of all drugs — including methamphetamine, cocaine, and fentanyl — a non-arrestable offense. And in early May, Oregon’s Canadian neighbor, British Columbia, amended its own previously liberalized rules, once again making the use of drugs in public an arrestable offense. This was after Washington had ended its own short-lived experiment last year.

To be fair, the research on the effects of decriminalization in Oregon and Washington, specifically, has been ambiguous. Dueling peer-reviewed studies using slightly different data find that decriminalization either increased or had no effect on the overdose death rate. A recent preprint paper argues that there really was no effect by controlling for the level of fentanyl penetration in the two states’ markets—statistically downplaying the effect of decriminalization on the spread of fentanyl.

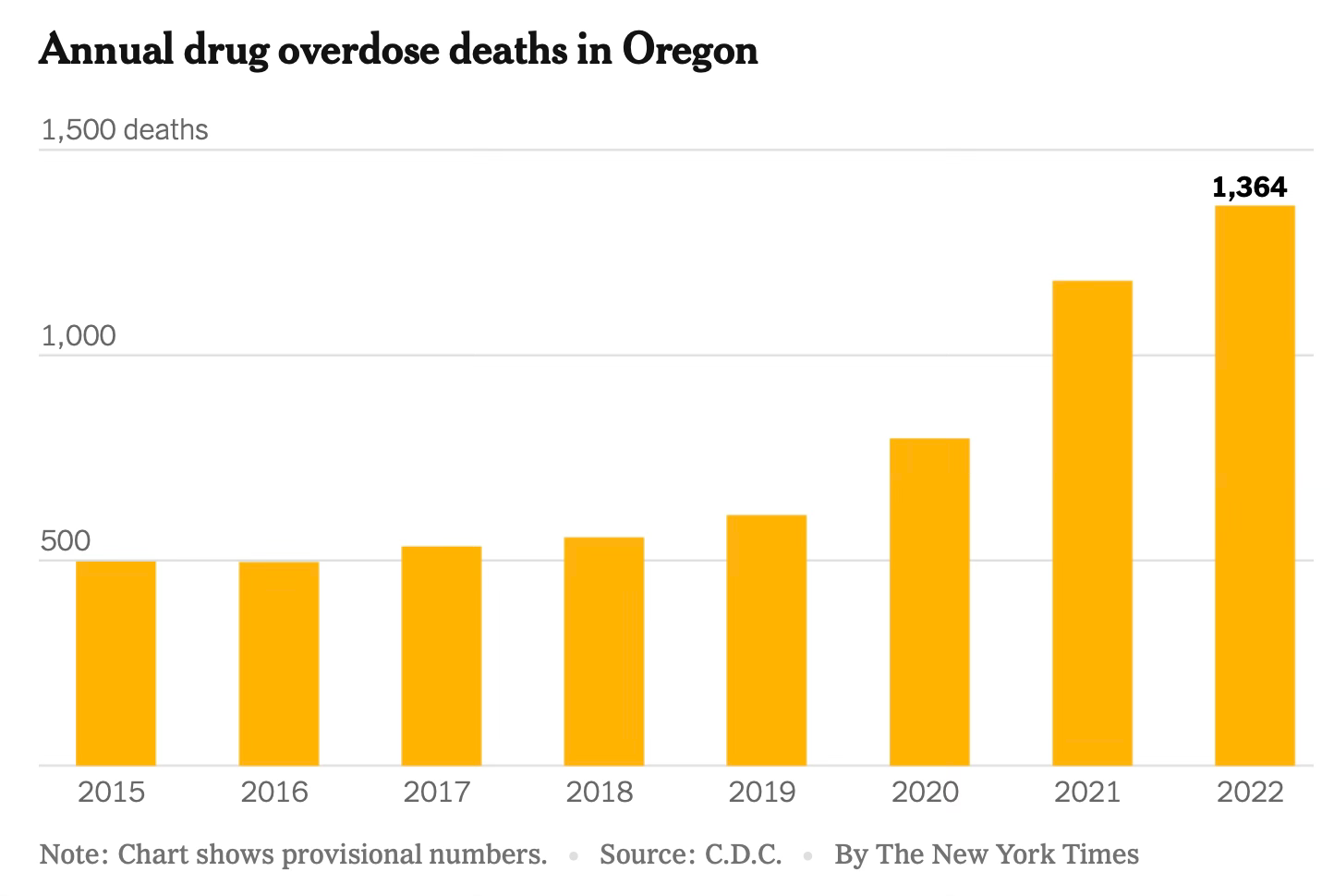

Yet it’s clear that the decriminalization experiment overall has not worked. Whether or not caused by decriminalization, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia experienced some of the fastest-growing overdose death rates in their respective nations. Residents, meanwhile, complained about the spread of uncontrolled public drug use and the disorder and petty crime which usually goes with it.

An analysis by RTI International (the authors of which include a leading proponent of harm reduction) shows an increase in property crime offending in Seattle and Portland following decriminalization, relative to Sacramento and Boise as “control” cities. (Addiction is a major driver of property crime.) While decriminalization was meant to help people get treatment, there’s little evidence that utilization went up. In Oregon, almost no one utilized the free hotline meant to provide drug users with help.

Proponents of decriminalization, though, have been quick to object that correlation and causation are not the same. The Drug Policy Alliance—a leading pro-reform group that poured millions into passing Oregon’s measure—has argued that the rise in drug overdoses following Oregon and Washington’s decriminalization was really the fault of “external factors,” including COVID and the spread of fentanyl to the west coast.

Even if they’re right, it’s irrelevant. The argument for decriminalization, after all, wasn’t merely that it would have no effect on public health and order. It was that policing drug possession substantially contributed to overdose deaths and other drug-related harms by discouraging people from seeking treatment for fear of legal consequences and by putting them in situations (jail, i.e.) where they would lose tolerance, leading to a fatal overdose. If the evidence is split between “did nothing” and “made things worse,” there is almost no reason to conclude that decriminalization made the Pacific Northwest’s situation better than it was before decriminalization.

This issue is particularly pressing amid a drug crisis that now takes over 100,000 lives a year. The War on Drugs represented one theory of how cops could help the crisis—by aggressively arresting and incarcerating dealers and users. Decriminalization represented another—cops could help most by staying out of the way. The fact that neither theory was borne out is cold comfort to the loved ones of those who have died.

The failure of these initiatives raises uncomfortable questions for the large majority of Americans who reject the War on Drugs. As the New York Times’s Ezra Klein recently put it, “The war on drugs was a failure. But so far, the war on the war on drugs hasn’t entirely been a success, either.”

Where, then, do we go from here? What role, if any, should police play in addressing the drug crisis? Are the only options a million drug arrests a year or no drug arrests at all?