The Reason We’re So Shocked By Deadly Floods Is Because We’re So Good At Preventing Them

Deaths and damages from floods in Europe have declined dramatically over the last 150 years

The floods in Europe that killed over 150 people in recent days were a result of climate change, many people say. “Deadly Floods Show World Unprepared to Cope with Extreme Weather,” read the front page headline of The New York Times. “‘No One Is Safe.’” Said a German climate activist, “This is the climate crisis unravelling in one of the richest parts of the world.” The country’s interior minister agreed. "This is a consequence of climate change," he said.

But the reason the floods were so deadly is because European nations were so unprepared for them. Last fall, the German government held a national “warning day,” when loud sirens and text messages were supposed to alert people to danger. “It was a debacle,” The Times of London reports. “Most of the technology didn’t work.” A professor of hydrology who helped build Europe’s flood prediction and warning network said there was a “monumental failure of the system.” She added, “We should not be seeing this number of deaths from floods in 2021."

And there is evidence that Germany failed to prevent dams from collapsing. “I noticed that, for the last three weeks, all the dams were just 20 – 30 centimeters from the brim,” a resident told a television reporter. “Why didn’t they release some of the water in a controlled way much earlier? This whole thing should not have happened if there had been 10 or 20% more available volume in the dams.” The reporter added, “That’s criticism I’ve heard again and again today.”

It’s true that flooding is affecting more people and more areas in Europe, and that a warming planet is likely to result in greater rainfall. Warmer air can hold more water, which makes it more likely that storms will produce more precipitation. “Extreme hydrological events,” noted a study of 150 years of European flooding in the journal Nature, “are generally predicted to become more frequent and damaging in Europe due to warming climate.” Observed one scientist, “Any storm that comes along now has more moisture to work with.”

But the best-available science does not find any increase in precipitation or in the cost of floods in Europe. “Though consensus seems to exist regarding the trajectory of future climatic developments,” noted the Nature authors, “there is less confidence in the changes in flood losses as a result of climate change so far. Qualitative and quantitative hydrological studies for Europe have indicated no general continental-wide trend in river flood occurrences, extreme precipitation, or annual maxima of runoff.”

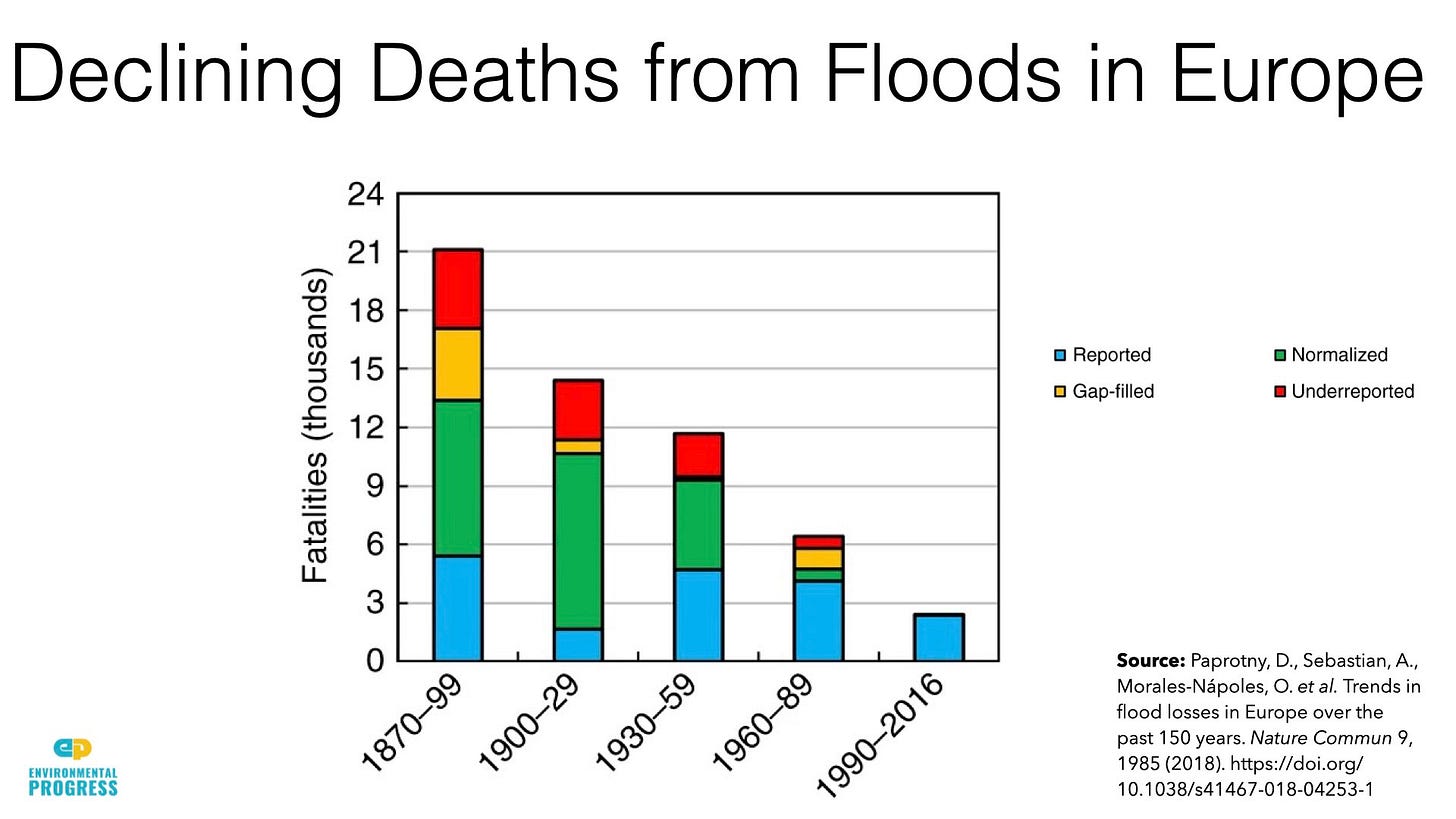

In fact, scientists find a significant decline in both deaths and damage from flooding in Europe, over the last 150 years. The overall cost of flooding increased, but when scientists account for greater wealth, scientists found “a considerable decline in financial losses” since 1870 that accelerated after 1950. What has changed is more people living in flood zones, and more paved areas, which means less ground to absorb excess water.

How can more people be affected by floods and yet fewer die? The reason is because we are so much better at managing them. Europe’s infrastructure has improved markedly. The Nature authors found that “areas with high concentration of urban fabric and infrastructure are better protected than less important urban zones, let alone rural areas. This is an intuitive conclusion, but supported by evidence from events spanning almost 150 years.”

In fact, the infrastructure improved so much that many Germans appeared to have grown complacent. “People knew an extreme weather situation was coming and that it could hit them,” said a government official who worked in the flood control system. “I think a lot of people clearly underestimated the weather warnings.” Said one of the creators of the flood warning system, “Probably they were like a fantasy or a kind of science-fiction movie for people.”

This reality appears to contradict the scholarly consensus that people tend to over-estimate rather than under-estimate rare events. Noted a scholar, “when asked to estimate the probability of a tail event, people tend to overestimate this probability.” For example, “people significantly overestimate the frequency of rare causes of death.”

But in other instances, people under-estimate rare events. One of the most famous cases was illuminated by author Nassim Taleb. In the run-up to the 2008 U.S. financial crisis, many investors believed the risks of severe collapse were low.

Why do some people overestimate some risks while others underestimate them? Does it just depend on the person? On the risk? Is it just random?

Part of the answer comes from something psychologists call the “availability heuristic.” People tend to evaluate the likelihood of an event based on how easily they can remember instances of it occurring in the past. Is the memory readily “available” or “unavailable”?

In 2007, it was hard for many people to remember a financial crisis like the one that was likely to occur. Likewise, it was hard for many Germans to remember flooding as bad as they experienced, and thus ignored the risks.

“The management of flooding around the world has been a great success story of the past 100 years,” noted Roger Pielke, Jr., a leading expert on the relationship between disasters and climate change. “But maintaining preparedness in the face of very rare events outside our experiences can be difficult. While the large loss of life we saw over the past week was not uncommon in Europe as recently as the 1960s, the last period of elevated flooding in western Europe was more than a century ago.”

Psychological research suggests political ideology likely plays a role. The people who live in the areas more likely to be flooded tend to be more rural, more conservative, and less alarmist. The people who live in areas less likely to be flooded tend to be more urban, liberal, and alarmist. “We’re at the very beginning of a climate and ecological emergency,” tweeted Greta Thunberg, “and extreme weather events will only become more and more frequent.”

Thunberg may be right. Greater warming is likely to bring more rain to some parts of the world. But it’s also the case that more rain is likely to become less deadly and damaging, as it has over the last 150 years.

There has been a 92 percent decline in the per-decade death toll from natural disasters since its peak in the 1920s. In that decade, 5.4 million people died from natural disasters. In the 2010s, just 0.4 million did. Globally, the five-year period ending in 2020 had the fewest natural disaster deaths of any five-year period since 1900.

The decline in deaths from disasters occurred during a period when the global population nearly quadrupled and temperatures rose more than 1 degree centigrade over pre-industrial levels. Even poor, climate-vulnerable nations like Bangladesh saw deaths decline massively thanks to low-cost weather surveillance and warning systems and storm shelters.

Such disasters will also make climate change even more of a “wicked problem,” meaning that many people have an interest in pointing fingers. Local officials have an interest in blaming the federal government for the failure of the flood warning system. Federal officials have an interest in blaming local governments for failing to properly manage dams. The designers and operators of the flood warning system have an interest in blaming individuals. Individuals have an interest in blaming anyone but themselves. And climate activists have an interest in blaming climate change.

“Of course, there is much more to do to reduce exposure and vulnerability,” said Pielke. “But the good news is that we know how to prepare for and mitigate the impacts of floods. That is a lesson of every flood disaster.”