The Infantilism Of Totalitarianism

Why the Meta-Facebook-Threads effort to make language safe is so dangerous

Mark Zuckerberg of Meta-Facebook-Instagram says he wants his new Threads app to be a more positive alternative to Twitter. "We are definitely focusing on kindness and making this a friendly place," Zuckerberg said on Wednesday.

In practice, that’s meant creating secret blacklists to censor disfavored users and selling your personal “Health & Fitness," "Financial," and "Sensitive" data to the world’s largest corporations and, perhaps, the military-industrial complex.

Some amount of censorship, or “content moderation,” is inevitable, but what Zuckerberg is doing is positively Orwellian.

It is not in the name of oppression that the totalitarians come but rather in the name of kindness. This is censorship with a smile.

And it was brilliantly predicted by Brendan O’Neill in an essay, “Words Wound,” in his new book, A Heretic’s Manifesto: Essays on the Unsayable.” We reprint it below.

All of those years of “microaggressions,” “trigger warnings,” and “safe spaces” has brought us to this moment of truth. With the Censorship Industrial Complex finally exposed, Zuckerberg’s Meta has emerged to implement it in a friendlier form.

And governments around the world, including in Ireland, are pushing for greater censorship in the name of preventing the harm ostensibly caused by the wrong words.

The calls for civility aren’t what they appear to be. They aren’t the pleas of people who want genuine exchange. They are the demands of those who want to shut it down.

Overcoming the present totalitarian censorship by Meta and the Censorship Industrial Complex won’t be easy. Still, at least there are Substack and Twitter, which have not engaged in the partisan and ideological censorship that Meta has.

Ultimately, we’re the ones who need to change. We need to start seeing the calls for “kindness” and “friendliness” online for what they so often are: calls for the world’s largest corporations to silence the political Other.

— MS

Words Wound

By Brendan O’Neill

Words hurt, they say. This is the ideological underpinning to so much censorship today – the idea that words wound as a punch might wound. The imagery of violence is deployed in almost every call for censure in the 21st-century West. Speech has been reimagined as aggression, hence “microaggressions.” People speak of feeling “assaulted” by speech. “Words, like sticks and stones, can assault; they can injure; they can exclude” – that’s the thesis of Words That Wound, an influential tome published in 1993.[1] Activists claim to feel “erased” by controversial or disagreeable utterances. Trans campaigners speak darkly of “trans erasure”, as if words from the other side of the divide, the speech of gender-critical feminists, might contain that most awesome and nullifying power of genocide.

Words make us feel “unsafe,” people say. Witness the rise and rise of Safe Spaces on university campuses, designed to ensure students’ psychic security against the terrible threat of their hearing an idea they disagree with. Safe Spaces recreate the state of childhood, complete with coloring books and ice cream, speaking to how determinedly some long to retreat from the adult world of hurtful chatter and brickbats.[2]

The United Nations wrings its hands over “hate speech and real harm” (my emphasis). The “weaponization of public discourse for political gain” can lead to “stigmatization, discrimination, and large-scale violence,” it says.[3] Better keep a check on those hurtful words. One US university even maintains a list of “words that hurt”. It includes the phrase “You guys”.[4] That scandalous utterance “erases the identities of people who are in the room” and “generalize[s] a group of people to be masculine”. Shut it down. Silence that act of violence.

Both the formal and informal punishment of words rests on the belief that they can wound. Laws in Europe claim to guard people from speech that is alarming, distressing, hurtful. The overlords of social media censor speech for “the well-being of our community”.[5] Everywhere the cry goes up: words injure, they can cut like a knife, they can be used as “weapons to ambush, terrorize, wound, humiliate and degrade”.[6] And just as the law protects us from such dreadful things when they are done to our bodies with fists and kicks, surely it should also protect us from them when they are done to our minds with words and ideas. Surely, our psychic wellbeing should be accorded as much respect by the powers-that-be as our physical integrity is.

The temptation of many of us who believe in freedom of speech, in the liberty of all to utter their beliefs and ideas, is to damn this claim that “words hurt” as a libel against public discourse. As a slippery untruth that is cynically designed to depict words as all-powerful, as containing so much energy, so much heat, that they can lay waste to self-esteem and even make us fret over erasure, over being wiped out entirely by that sore comment or that disturbing idea. Actually, we often say, words are just words. They’re not sticks, they’re not stones, they’re words. They won’t kill you, they won’t hurt you, you’ll be fine. They say words are a force of nature like no other, we say: “Relax. It’s just speech.”

We need to stop doing this. We need to stop countering the new censors by accusing them of exaggerating the power and the potency of words. We need to stop responding to their painting of speech as a dangerous, disorientating force by defensively pleading that words don’t wound because they’re just words. We need to stop reacting to their branding of speech as a weapon, as a tool of ambush and degradation, by effectively draining speech of its power and saying: “It’s only speech.” As if speech were a small thing, almost an insignificant thing, more likely to contain calming qualities than upsetting ones, more likely to help us overcome conflict rather than stir it up, more likely to offer a balm to your soul than to stab at it as a knife might stab at your body.

For when we do this, we play down the power of words. And that includes the power of words to wound. Words do wound. It’s true. Words hurt people, they hurt institutions, they hurt belief systems. Words make churches tremble and ideologies quake. Words inflict pain on priests and princes and ideologues. Words upend the social order. Words rip away the comforting ideas people and communities might have wrapped themselves in for decades, centuries perhaps. Words ambush the complacent and degrade the powerful. Words cause discord, angst, even conflict. Isn’t every revolution in history the offspring of words? Of ideas? Words do destabilize, they do disorientate. People are right to sometimes feel afraid of words. Words are dangerous. When they say words wound, we should say: “I agree.”

But here’s the thing: it is precisely because words can wound, precisely because of their power to unsettle, that they should never be restricted. It is precisely the unpredictable energy and influence of speech that means it must be put beyond the jurisdiction of all earthly authorities. Because nothing that empowers the individual to such an extent that it allows him to sow and spread ideas that might one day change society for the better should ever be constricted. They say the power of speech justifies its censure and control. We should say the opposite: the fact that speech is powerful is all the justification we need to let it be free, everywhere and always.

We must point out that where words hurt – and they do – censorship hurts more. Physically, spiritually, and existentially, censorship is more wounding to the individual and to society than unfettered speech is. Those in the 21st century who claim to feel bruised and bloodied by words should take some time to read up on the heretics of history and even the heretics of today. You want to see wounding? Witness their trials.

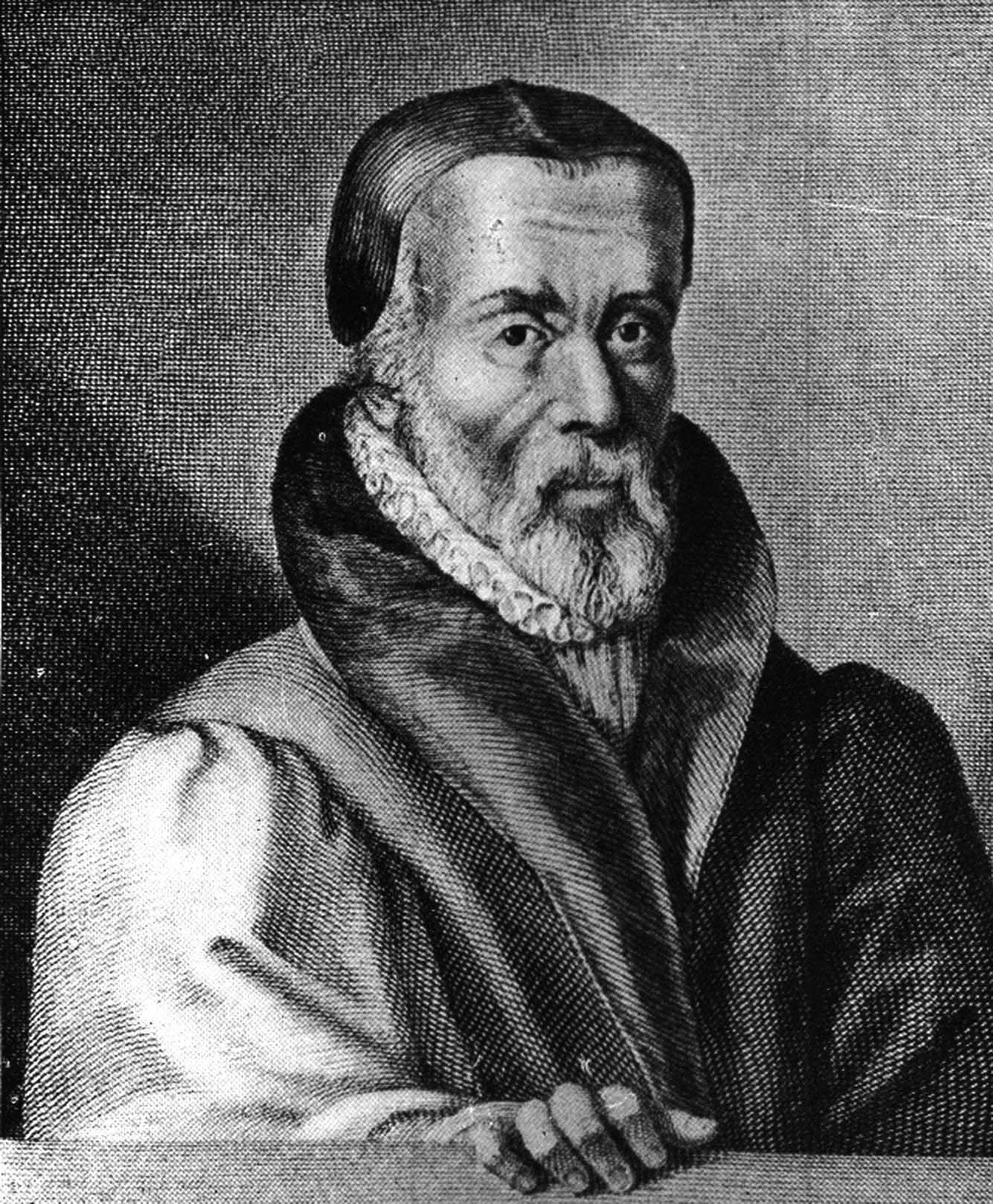

They Risked Their Lives For Free Speech