How We Saved Diablo Canyon Nuclear Plant

Excerpts From City Journal

Jim Megis of City Journal has published an account of how a small group of us saved Diablo Canyon nuclear plant. In my next book, The War on Nuclear: Why It Hurts Us All, I will describe in detail why and how we have saved nuclear plants all over the world. Until then, this is an inspiring short overview. Below is an excerpt.

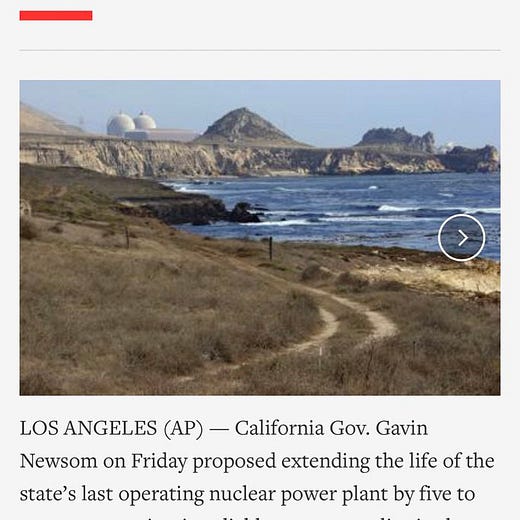

Last week, California governor Gavin Newsom announced a plan to roll back the planned retirement of Diablo Canyon, the state’s only surviving nuclear power plant. For several months, Newsom had been tentatively exploring options to keep the San Luis Obispo plant running. Nonetheless, the announcement was something of a shock. After all, not so long ago, the governor had helped lead the political movement demanding that the plant be closed. And until quite recently, California’s elite class—lawmakers, journalists, entertainers—were almost unanimously opposed to the very idea of nuclear power, seeing it as a risky and unnecessary distraction on the road to bounteous wind and solar power.

How did this rapid change in public opinion come about? In some ways, California’s sudden embrace of nuclear power recalls the famous quotation attributed to Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of committed citizens can change the world; indeed it is the only thing that ever has.” Though the quotation is probably apocryphal, it captures the way a tiny cohort of pro-nuclear advocates made their case, plugging away year after year, gradually winning both policymakers and the public to their side.

“It was very lonely at first,” recalls Michael Shellenberger. In 2016, when California’s Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) announced plans to retire Diablo Canyon, he was one of the handful of environmentalists to speak up in defense of the plant. Their viewpoint wasn’t popular. “We were demonized and accused of all sorts of terrible things,” he told me.

The Back Story

Diablo Canyon had always been a lightning rod for criticism. Thousands protested the plant’s construction in the early 1980s; singer Jackson Browne was among the many arrested trying to block the gates. The Los Angeles Times called the demonstration “the Normandy Invasion of civil protests.” Even after the plant opened in 1985, environmental groups, including Friends of the Earth and the Natural Resources Defense Council, kept fighting to shut it down.

In 2013, Senator Barbara Boxer, Friends of the Earth, and other anti-nuclear advocates forced the early retirement of California’s San Onofre nuclear plant near San Clemente. By 2016, environmentalists were successfully running the same playbook on Diablo Canyon. Legal activists tied up PG&E with lawsuits, while state officials—including then-lieutenant governor Gavin Newsom—looked for bureaucratic maneuvers that would force the company to close the plant. They knew that by 2025 PG&E would need to get the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s (NRC) approval to extend Diablo Canyon’s operating license. They vowed to do everything they could to block that process. (New York governor Andrew Cuomo, working with Riverkeeper and other anti-nuclear activists, used similar tactics to force the closure of the Hudson Valley’s Indian Point power plant in 2021.)

Finally, PG&E threw in the towel, announcing it would not seek a license extension. The embattled power company promised it would replace the plant’s 2,200 megawatts (nearly 9 percent of California’s electricity) with renewable energy projects.