Dark Side Of Destigmatization

No human being should be stigmatized. But untreated mental illness and addiction are dangerous and destructive, and should be.

“It is time to end all forms of stigma and discrimination against people with mental health conditions,” editorialized the prestigious British medical journal Lancet yesterday. The editorial accompanied a special, 43-page report by 50 co-authors on ending stigma and discrimination against “people with lived experience of mental health conditions (PWLE),” which it called “worse than the condition itself.” The special report concludes that “our single, simple key message is the following: mental health is part of being human, let us act now to stop stigma and to start inclusion.”

In truth, efforts to avoid stigma and discrimination against mentally ill people have been going on for decades, including in the criminal justice system, where judges routinely consider the mental health of criminal suspects. Consider the following cases:

In 2017, a Chicago judge ruled that Jawaun Westbrooks was not guilty for reasons of insanity after attacking two 55-year-old women with a hammer and ordered him hospitalized until 2021, when he was released.

In 2019, a Montgomery County court in Maryland dismissed several trespassing cases against Eliyas Aregahegne, a mentally ill 24-year-old man, and put him on probation.

And in March of this year, a judge in southwestern Washington released John Cody Hart on “supervised release” despite the stigmatizing, discriminatory appeal of the local prosecutor, who said: “the Community does not need somebody suffering from untreated mental illness out committing unprovoked serious violent offenses.”

But in each of the above cases, what happened next challenges Lancet’s contention that stigma and discrimination are “worse than the condition itself.”

In early September last year, not long after being released from a psychiatric hospital, Jawaun Westbrooks walked into a Chase Bank and stabbed Jessica Vilaythong, 24, a bank teller, as she spoke with customers. Then, Westbrooks ran outside and waved his bloody knife while screaming at passers-by.

In late August 2019, Eliyas Aregahegne ran up to Margery Magill, 27, a paid dog walker, and stabbed her in the stomach, neck, and back. Detectives followed a trail of blood from her body to an apartment a quarter-mile away where Aregahegne was watching TV.

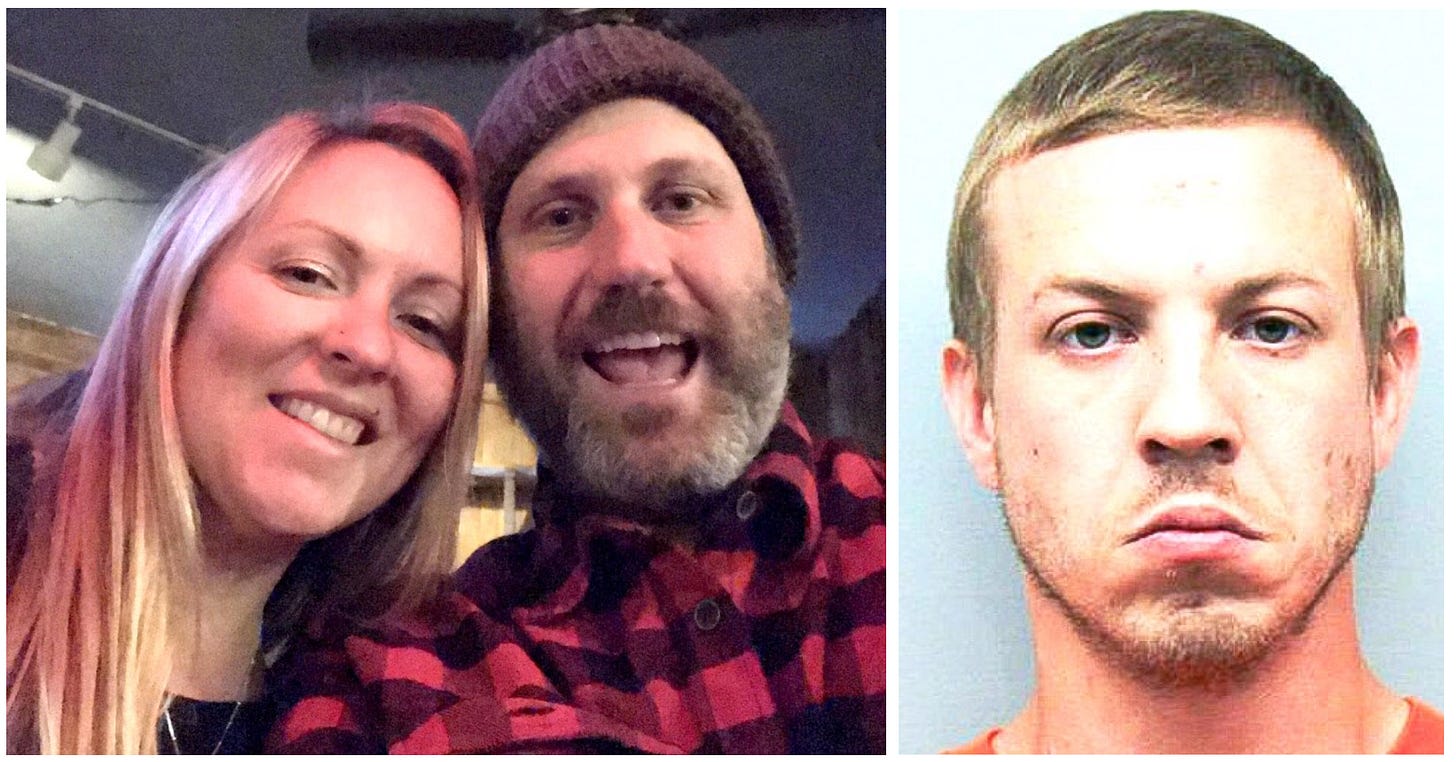

Last Saturday, John Cody Hart shot Rory and Sara Mehen, two 40-something innkeepers, at point-blank range after they confronted him stealing from other guests. Hart told detectives that he felt humiliated by the Mehens and heard the voice of Pope Gregory and John Paul say to him, “Are you going to let Bonny and Clyde do that to our family?”

The authors of the Special Lancet Report boast that it was “co-produced by people who have lived experience of mental health conditions,” contains six poems (e.g., “Mental health is part of being human”), and includes testimonies “to bring alive the voices of people with lived experience.” But nowhere does it mention the fact that people with lived experience of mental health conditions, particularly ones with substance use disorder, have, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association, “a significantly increased probability of having a history of violence.”

Without question, people who have mental illnesses merit our empathy. Severe mental illness is disabling, preventing people from engaging in regular work or family life. Adults with serious mental illness are more likely to suffer from substance use disorder and numerous general health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory infections, complicating their care needs. According to the World Health Organization, serious mental illness reduces life expectancy by ten to twenty-five years, primarily due to chronic physical health conditions and suicide.

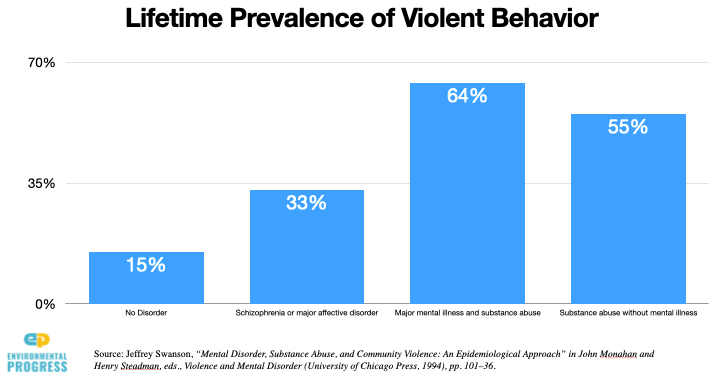

And those with mental illness are: a fraction of violent offenders; more likely to be victimized than victimizers; and at greatest risk when self-medicating with drugs or alcohol. People with serious mental illness are more likely to be homeless, interact with drug dealers, and be raped, beaten, or otherwise victimized than the general public. Somewhere between 7% and 56% of mentally ill people are estimated to be victims of violence. And if the elevated risk of violence among the mentally ill were reduced to the average population risk, researchers estimate that 96% of the violence that currently occurs would continue to happen.

But nobody doubts the higher prevalence of violence among the mentally ill, the 96% number is deeply misleading, and America’s addiction crisis doesn’t diminish the risk of violence, it increases it. The 96% number does not differentiate between severe forms of violence, like murdering strangers, and more benign acts, like threatening a family member. As for drugs, researchers note, “The highest risk was shown for dual-disordered [mentally ill and addicted] subjects with a history of violence, who showed nearly 10 times higher risk of violence compared with subjects with severe mental illness only.”

Such may have been the case with John Cody Hart, a transient Army veteran. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia and a marijuana use disorder after nearly killing a man in 2021. Indeed, a photo on his Instagram shows him smoking a blunt. On Aug. 9, 2021, Hart jumped on a man, put him in a vascular neck restraint, and pressed his thumbs so hard into the man’s eyes that he will likely remain blind for life.

The murders by Hart, Aregahegne, and Westbrooks undermine the central contention of Lancet that stigma and discrimination against the mentally ill are “worse than the condition itself.” Murder is worse than the condition itself. And, against the overall tenor of the Lancet report, the research on this subject is clear. “We can’t go out and lock up all the socially awkward young men in the world,” notes Jeffrey W. Swanson, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University. “But we have to try to prevent the unpredicted.” Or, as JAMA researchers wrote, “review of this data demonstrates that the link between mental illness and violence is clearly relevant to violence risk management in clinical practice. This link should not be understated or ignored.”

And yet that’s precisely what Lancet did. Why is that? Why would Lancet, a journal supposedly committed to scientific rigor, medical ethics, and victims’ rights, totally ignore the good reasons people have for stigmatizing untreated mental illness?

The War On Psychiatry