Behind Push To Legalize Government Drug Dens, $300+ Million Soros Investment

Amazing what a little money will get you

In Hunter Biden’s 2021 memoir, Beautiful Things, he recounts the day his parents staged an intervention to save him from his addiction. He stormed out of the house as his daughters tried to block him from getting into his car. President Joe Biden chased him down the driveway. “He grabbed me,” recounted Hunter, “swung me around and hugged me. He held me tight in the dark and cried for the longest time.”

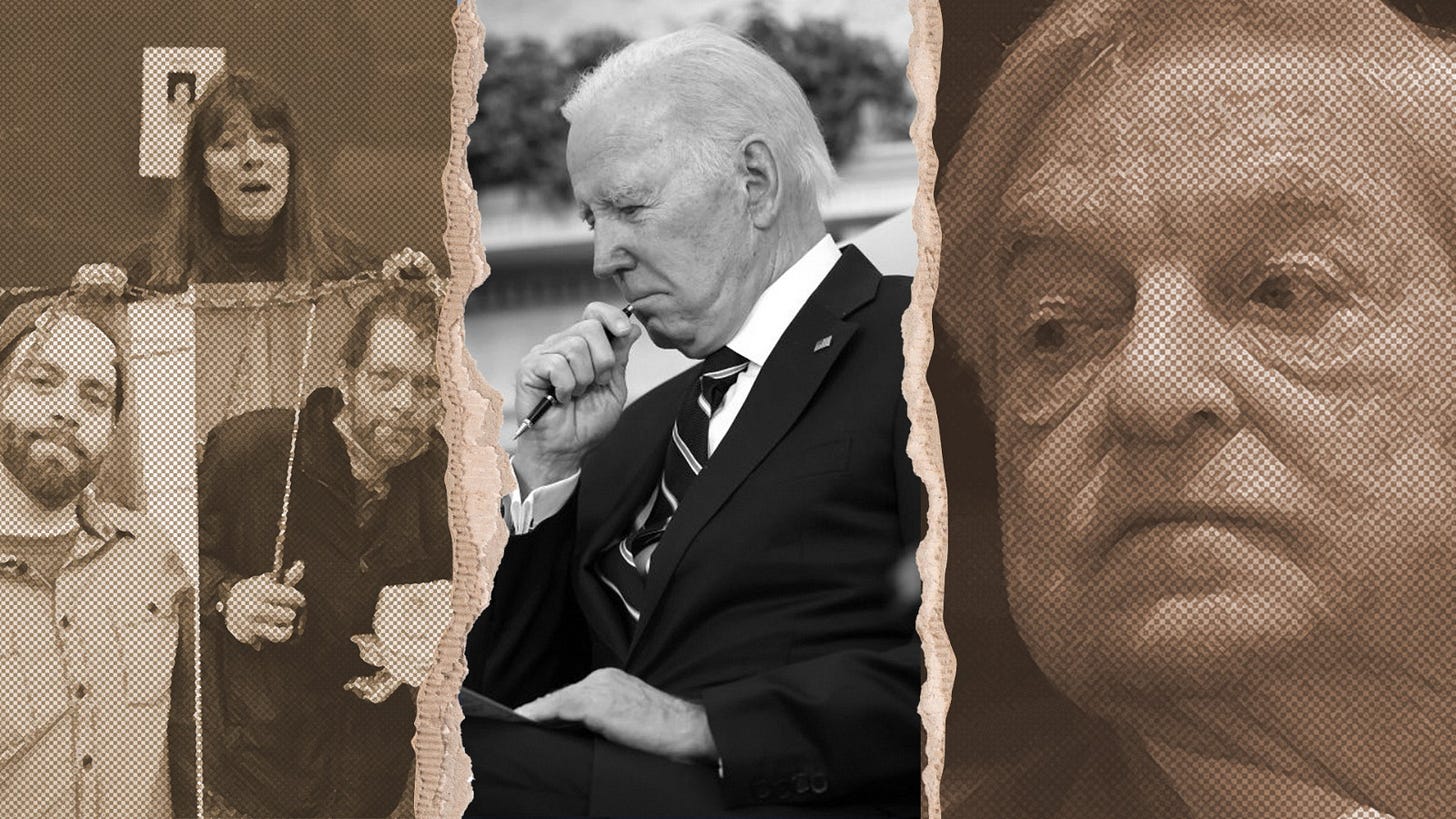

Perhaps more than any president in US history, Joe Biden understands addiction’s awesome and awful power. Nobody should be more sensitive to the issue of addiction than he. For years, he and others in the Biden family struggled to get Hunter into treatment and recovery. The President knows, better than most Americans do, that many hard-core drug addicts require an intervention, not enabling.

And yet President Biden’s Justice Department is actively considering legalizing government-funded drug dens, which would enable addiction, not recovery. In early December, the DOJ told a Philadelphia judge that it would decide within two months whether to grant the city a waiver from federal law so it could operate a government-funded drug site.

Supporters of government-funded drug dens say they will save lives lost to overdose. The drug addiction crisis is the worst public health crisis in the United States. Illicit drug deaths rose from 17,000 in 2000 to 107,000 in 2021.

Government drug sites are modeled on what they do in the Netherlands and Harlem, which are currently operating sites. The operator of the Harlem site testified to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors that the New York site had saved lives without any impact on the community.

But the Netherlands pressures destructive and self-destructive addicts to get into rehab and recovery communities, which the U.S. does not have and Biden is not proposing to build. The Harlem site has attracted, not reduced, open-air drug use and drug dealing, residents say. And overdose deaths rose precipitously in Vancouver, B.C., alongside supervised drug consumption sites.

Past Democratic politicians recognized that many addicts won’t seek treatment unless required. “The problem of homelessness is not going to be solved,” wrote former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown in his memoir, “until one major drastic change takes place in public policy: we have to be able to impose help and treatment on people.”

Biden himself had historically been opposed to open drug use. In 1986 he cosponsored the “crackhouse statute,” which made it illegal to “knowingly open, lease, rent, use or maintain any place, whether permanently or temporarily, for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing or using any controlled substance.”

Keith Humphreys, the lead author of last year’s Lancet-Stanford Commission on the Opioid Crisis, argues that intervention, if not by family then by the police, is often necessary for getting addicts into treatment. “A lot of people are addicted,” he said, describing homeless addicts in San Francisco, “and don’t want to change until it hurts.”

And many parents of addicted homeless children want the courts to mandate drug treatment and rehabilitation, as they used to, before the passage of Proposition 47, which decriminalized possession of three grams of hard drugs, in 2014.

“I think Corey might need mandatory intervention,” said Jacqui Berlinn, co-founder of Mothers Against Drug Addictions and Deaths, about her son, who is a homeless fentanyl addict. “I get a lot of pushback. It’s the old adage of, ‘You can’t force them,’ and to some extent, I believe that. But honestly, everybody’s different, and my son’s rock bottom is death.”

There is little doubt that if President Biden were to meet with Berlinn, Humphreys, or any of the recovering addicts who co-founded the new North America Recovers coalition, he would agree that many addicts need an intervention. Why, then, might Biden sign off on “modern day opium dens” that enable addiction?

$300 Billion Explains A Lot